Posted: 2/29/16

Words by: Maarten Van Praag

The beginning:

The very first seed of this story was planted, kind of accidentally, three decades ago. It was sometime in the early eighties during the times of Eastern European Communism and the Cold War. It was then that a couple of employees of the state owned truck manufacturer LIAZ first heard of “the Dakar” and got really excited about this marathon race. Being adventurous and stubborn, they decided to do something quite impossible – tried to persuade Viktor Korecky, LIAZ Director, that this really was a great idea. They actually bugged him long enough and somehow succeeded at the end!

Coincidentally at that same time, the strict regime was weakening and the comrades were looking for more opportunities to sell more socialists products abroad in order to support the falling economy. One of the ways to do this was export through the company called M.A.M Strager, based in France. From the sources I have, I know that Viktor Korecky must have been a bright and adventures guy as he managed to push this insane semi-official project through the governmental bureaucracy.

Of course, this is a very short version of the story and there were many others involved, but what is important, finally it was decided that LIAZ will participate in Dakar 1985.

This was not the end, as many would hope. Our small group of excited employees started to get quite worried as they woke up from a dream and started facing a number of responsibilities and real challenges, many of them that people who have not seen Communism could ever hardly imagine.

In short:

1) The project was kind of “not so official” = lack of funding, no real support from…anyone

2) The product (LIAZ trucks) was not exactly known for advancement and reliability = trouble guaranteed

3) They had no pieces of racing equipment available = not exactly an ideal starting point for participation in one of the toughest races in the world

4) They had questionable support from the factory = working mostly with leftover parts that they gathered

5) They only knew a real Dakar truck from a magazine = they knew nothing

6) They were forced to “volunteer” to do this themselves (“You came up with this, you do it approach”; most people thought they were insane and did not want to get dragged down… just in case it all fails) = unpaid nightshifts; free time and weekends gone

7) They were in an isolated country = no information, no travel allowed, no suppliers from abroad, bureaucracy, no real international cooperation except for M.A.M Strager (which really helped, in the end)

The race:

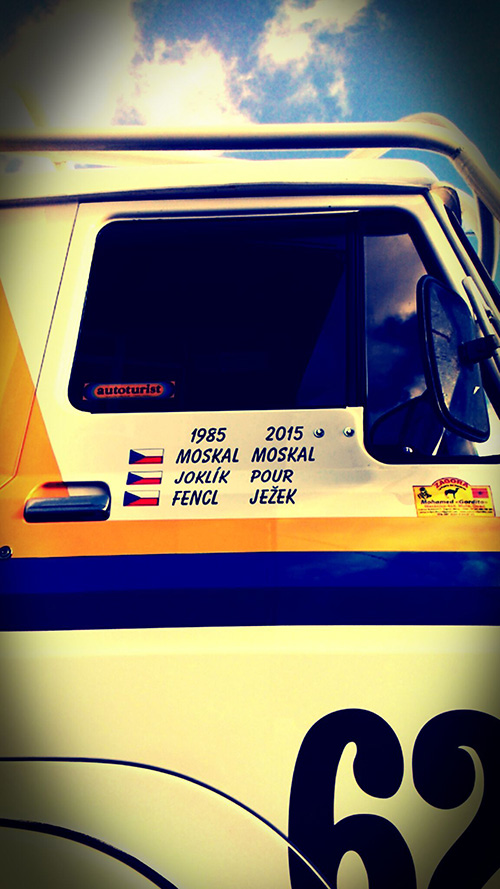

In the end, they managed to put together two trucks (#626 & #627) and selected 6 crew members, 5 Czechs and one Frenchman, supplied by M.A.M Strager. Support trucks as well as mechanics, as we know it from contemporary Dakar, were not included. The few testing sessions took place in the local fields. Without much attention from the public and media, something they appreciated just in case it goes wrong, they were finally ready to head towards Paris.

Their joy did not last long, however. They got stopped by the police right at the German border as nobody knew that trucks are not allowed on road in Germany during weekends and holiday…

Obviously, they were not allowed to continue, however, they were not even allowed to come back due to difficult paperwork and customs. The only option was to wait for the morning in the cabin. As it was an extremely cold winter night, they appreciated the fact the trucks were not stripped of heating. Not for long, however, the police were back and explained that idling is not allowed either…

The joy of racing did not, unfortunately, last long either. #627 soon lost rear dampers completely, both trucks suffered serious issues with steering and geometry of front wheels. The conditions appeared to be much worse than anticipated. On top of it, Allain Galland, the Frenchman from #626 started to seriously worry and decided to quit. #626 was out of the race due to an incomplete crew. #627 was falling apart but kept struggling through the challenges for another two weeks. At that point everyone present started regretting this stupid idea.

It must have been the power of will, combination of luck, and insanity that caused #627 to actually finish the race… and, in fact, placed 13th! In the end, this became a hugely unexpected stepping stone that many others followed in the coming years. Today, 31 years later, there are 17 Czech crews on the start of Dakar, many of them respected internationally. For many, Rally Dakar has become one of the national sports.

LINK: https://jardakar.rajce.idnes.cz/Dakar_85_LIAZ_627/ (personal collection from the co-driver, JAROSLAV JOKLIK)

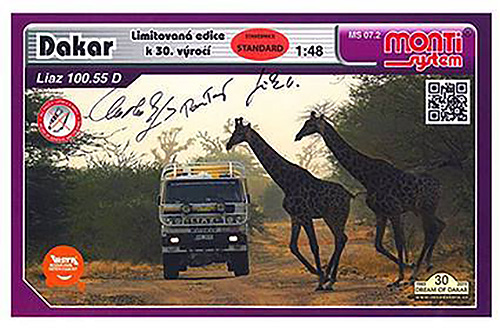

My connection to the #627

The “spirit” of #627 quickly became famous. A poster in every boy’s room was at that time almost mandatory, they even started to make a small model kit that became a super-popular Christmas gift for every boy and young man. However, the #627 itself was forgotten and stayed parked in the courtyard behind the factory. This famous vehicle that survived the impossible was suddenly left there rusting.

A couple years later, when the Iron Curtain was fresh history, this car attracted another semi-insane guy who decided to purchase it, take it all apart and build it again himself. He repeated the process again in 2014, just before the 30th anniversary of the race.

LINK: https://www.liaz.cz/liaz_dakar_85_opet_na_dakaru_2014.php (2nd renovation photo gallery)

On December 27, 2014 this legendary #627 stood on a square in Prague surrounded by people ready to depart to Paris. Jiri Moskal, the original driver, Tomas Pour, the owner, and his friend Vit Jezek, were ready for a memorial expedition to Dakar. The #627 went 15000 km before successfully returning home.

A Couple of months ago, I was lucky enough to meet Mr. Pour who showed me the truck in detail and even gave me and my friend a ride. It was then when I decided that my next rig will be #627.

Wish me the best of luck!

Martin

Follow this link for Part 2: https://www.axialadventure.com/blog_posts/1073915885